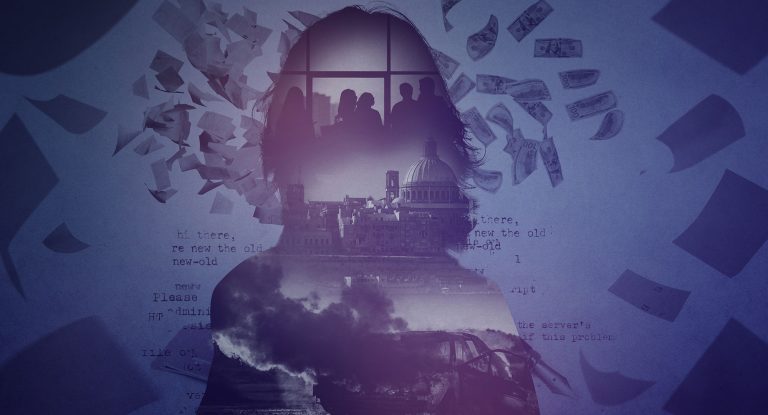

The Daphne project

When a reporter is murdered, we must take over their investigation

Journalists collaborated, and those who tried to halt Daphne Caruana Galizia’s work in Malta will soon know they failed.

By Laurent Richard

April 16. 2018

This opinion piece was published in The Guardian

You killed the messenger. But you won’t kill the message.

Over the past six months 45 journalists from 15 different countries have been working in secret to complete and publish investigations by the Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, who was killed on 16 October 2017.

Cooperation is without a doubt the best protection. What is the point of killing a journalist if 10, 20 or 30 others are waiting to carry on their work? Whether you’re a dictator, the leader of a drug cartel or a corrupt businessman, exposure of your crimes is your biggest fear. Journalists are the enemy of the corrupt ecosystem that you have constructed. But what if this exposure becomes global, and the message amplified? Wherever you go, you will be questioned by the world’s press. Whatever you are trying to hide will be magnified.

And this is the mission of our new international platform, Forbidden stories: a network of journalists who are ready to take over whenever a journalist is imprisoned or assassinated. The idea is to ensure the survival of stories.

The 45 journalists who collaborated on the Daphne Project, including reporters from the Guardian, have one clear goal: to inform the public about corruption and money-laundering in Malta, within the European Union, drawing on evidence that Daphne Caruana Galizia courageously revealed over the course of 30 years.

Daphne Caruana Galizia’s murderers must know they failed. They took the life of a 53-year-old journalist and mother of three children. But whoever ordered her murder, wherever they may be today, has lost. In the coming days, the latest investigations that she was working on will be shared with millions of citizens around the world.

The Daphne Project is the first Forbidden Stories cross-border investigation – a venture I started three years ago, after a tragic event.

On 7 January 2015, my office neighbours, the journalists and cartoonists of Charlie Hebdo, were massacred by terrorists from Yemen’s al-Qaida branch. The office of the press agency where I am working, Première Lignes, was just opposite Hebdo’s. By chance, I arrived at the office a few minutes after the assailants had left. As I reached the offices of Charlie Hebdo, I was faced with the horror of seeing colleagues lying suddenly silent, motionless, dead.

In 20 years of work I have covered several conflicts, including Iraq and Kashmir. I’ve investigated dictatorships. But this time it had happened in my close environment. Journalists killed for their drawings. This experience convinced me of the need for a “journalistic” response to crimes committed against the press. To defeat censorship through collaborative journalism.

In creating our platform, we have been inspired by similar initiatives. In 1976 the American journalist Don Bolles was killed when his car exploded in Phoenix, Arizona. In the days that followed, Investigative Reporters & Editors brought together 38 journalists from around the US to finish the investigation that the Arizona Republic journalist had started. In 2015, when the investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova was locked up in Azerbaijan, a dozen colleagues from the Organised Crime Corruption Reporting Project also pursued her investigation into the corruption and tax evasion of the ruling family in Baku. Just as courageous were the journalists from the Brazilian nonprofit organisation, ABRAJI, who carried on the work started by the reporter Tim Lopez, who was burned alive in 2002 by drug traffickers in a favela in Rio de Janeiro.

In 2018, journalists continue to be murdered for their work on toxic waste trafficking, tax evasion, corruption and human rights violations. This censorship is depriving millions of citizens of information that is fundamental for their societies and the future of their countries.

It’s up to us journalists to ensure a “Streisand effect” for these investigations that have been suppressed. In 2002, when the singer, Barbara Streisand filed a complaint to remove images of her Malibu home from a website site about erosion of the Californian coast. Filing a complaint was a huge mistake. Not only did the Californian court rule in favour of the defendant, but the very process that Streisand had started attracted curious eyes. After her lawsuit, the site in question had been visited 400 000 times, whereas before she filed a complaint it had had only had six visits, two of them from her own lawyers. The Streisand effect is at the very core of Forbidden Stories: journalism to defend journalism. With this kind of solidarity, we can ensure that investigations survive.

Even if you succeed in stopping a single messenger, you will not stop the message.

See also