- Temps de lecture : 12 min.

The front companies robbing the State of Mexico

In August 2021, Mexican journalist Maria Teresa Montaño Delgado was kidnapped while investigating public sector fraud in Mexico. Continuing her investigation, a consortium formed by Forbidden Stories is now revealing the signing of dozens of contracts totaling nearly €280 million, awarded to front companies through public biddings.

Disponible en

By Aïda Delpuech

Avec Mariana Abreu.

Translated by Gregor Thompson with Mariana Abreu.

Additional reporting by Maria Teresa Montaño Delgado (The Observer), Lilia Saúl Rodriguez (OCCRP), Nina Lakhani (Guardian US), Paloma Dupont de Dinechin, Sofía Álvarez Jurado, and Karine Pfenniger

With a trembling voice, Maria Teresa Montaño Delgado recounted the event that changed the course of her life. “It was a late afternoon, in the middle of August 2021,” she began. As she was leaving a medical appointment, the journalist based in Toluca, the capital of the State of Mexico (commonly known as Edomex), hailed a taxi to head home. Inside, she was assaulted by three armed men who blindfolded her and tied her up. They threatened Montaño with a gun, saying “you know very well what it is about.” The men then drove to her house. They already knew the address.

“They kept asking me, “Are you a journalist? What media do you work for?” Montaño said. Despite being terrified, she denied their allegations. “If I admitted I was a journalist, I’m convinced they would have killed me.”

Once they arrived at Montaño’s home, the kidnappers refused to let her enter and rounded up all her work equipment–her computer, voice recorder, camera, tablets, notebooks, and several years worth of documents–as well as her car. After several hours of torture, Montaño was freed.

“It was horrible, I thought they were going to shoot me. I said goodbye to my life; I said goodbye to my children,” she said, still shaken.

A few months before the kidnapping, Montaño, the founder and editor-in-chief of the Mexican investigative website The Observer, had been investigating public contracts in the State of Mexico–the country’s economic powerhouse. She noticed that several of the contractors were located hundreds of kilometers away. The contracts had multiple irregularities. Suspecting these were front companies created to embezzle public money through fake contracts, Delgado set herself on a mission to investigate the suspect contractors.

After her kidnapping, Montaño grew cautious; she paused her work and was granted a security escort. But she scoured the country nonetheless, following the trail of the companies behind the irregular contracts. To protect her work, she contacted Forbidden Stories, whose SafeBox Network allows threatened journalists to protect sensitive information. Our months-long investigation used documents, interviews and on-the-ground reporting to reveal that the State of Mexico signed 40 contracts with at least 15 front companies, amounting to nearly 5 billion pesos (€280 million), between 2018 and 2022. Some of these contracts involved individuals already linked to other major corruption cases, as well as senior representatives of the Partido Revolucionário Institucional (PRI), the political party that has ruled the State of Mexico for nearly a century.

Journaliste menacé

A journalist swimming with sharks

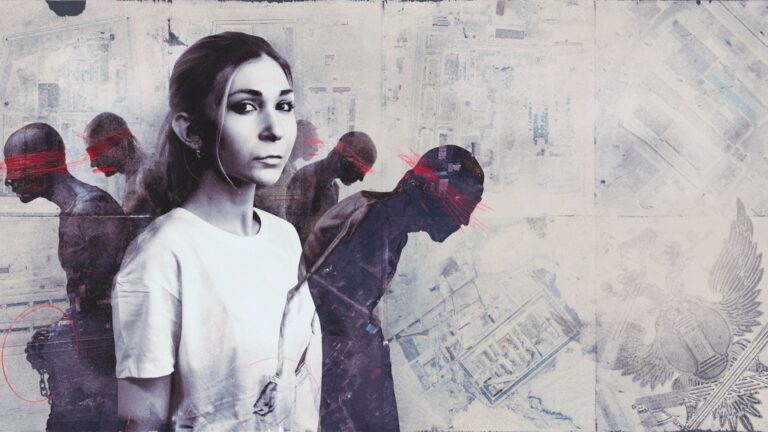

With her gentle gaze and soft voice, it is hard to imagine Maria Teresa Montaño Montaño as one of the journalists most feared by the State of Mexico’s political elite.

The state of 17 million people, located in the center of Mexico, close to the capital Mexico City, has the second largest economy based on GDP. It is also one of the PRI’s last strongholds. The political party, described as a “perfect dictatorship” by Peruvian Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa, has governed the State of Mexico since 1929.

There will be decisive local elections in the State of Mexico on June 4, 2023, which could put an end to the PRI’s reign. These elections are also expected to influence the 2024 presidential election.

“The State of Mexico has a strong symbolic and political value for the PRI and the opposition,” Rogelio Hernández, a political science researcher at the Colegio de México, told The Guardian.

In the State of Mexico, “a large part of the population lives below the poverty line, and public money is embezzled through front companies and irregular contracts. It’s a mafia,” Montaño said.

For years, she has exposed corruption through her investigations.

Maria Teresa Montaño Delgado says she was fired because of her “troublesome” work (Photo: Ginette Riquelme/ The Guardian)

In 2021, Montaño suspected a network of corruption was financing a political campaign. She spent several months downloading and analyzing more than 200 contracts that the State of Mexico signed between 2018 and 2022. The documents were accessible through IPOMEX, a state database initially created for transparency.

Montaño had discovered similar patterns in investigations in other Mexican states. She was convinced that some of the companies cited in the records were ghost companies that existed only on paper and had no employees or activity. She traveled around the country, visiting locations named in the contracts.

“I found it strange that the State of Mexico, the most industrialized in Mexico, was using companies located on the other side of the country,” she said. “I discovered that many of these companies have fictitious headquarters.”

Suivez-nous et partagez

nos histoires

22,000 electric grills for skincare workshops

Between 2021 and 2022, a cleaning company called Sevacom was awarded 12 public contracts that amounted to a total of more than 90 million pesos (€4 million). The company was tasked with organizing “make-up,” “skincare,” “sewing” and “balloon decorating” workshops in the State of Mexico. However, according to the contracts, the company is based in Guadalupe–some 900 kilometers from the State of Mexico.

“It is very strange to use a company that is based so far away given that these kinds of products can easily be found in Mexico,” Montaño said.

Following her suspicions, she went to Guadalupe to investigate the company’s offices.

When Montaño arrived, she discovered a modest shop with a blue front, selling cleaning products in bulk—a stark contrast from the value of millions of euros indicated in the contracts. According to its website, created a month after the contracts were signed, the company is “present on the national market” and offers more than 8,000 cleaning products.

When Degaldo questioned the shop owner, she denied signing any contract with the State of Mexico. Forbidden Stories and its partners have not found any online traces of the workshops detailed in the contracts.

Following Forbidden Stories’ requests for comment, the State of Mexico provided the consortium with several files, containing a variety of pictures and certificates, all of which fail to provide proof of service beyond a reasonable doubt.

The company, which specializes in the “sale of cleaning products,” suspiciously does not correspond to the business described in the contract, whose services are simply listed as “assistance and cooperation.” The contract also mentions absurd orders, such as 22,000 “electric grills” for a skincare workshop.

Contacted by the consortium, Sevacom did not reply to requests for comment.

Our investigation also revealed that major figures from the State of Mexico PRI party are involved in these contracts. Two of the 12 contracts were issued by the Secretariat of Labor and Social Welfare (SEDESEM) of the State of Mexico, a public department tasked with fighting poverty and reducing inequality.

At the time the contracts were signed, Eric Sevilla Montes de Oca, the current president of the PRI in the State of Mexico, headed the department. Alejandra del Moral, PRI candidate in the upcoming local elections and former PRI president in the State of Mexico, then replaced Montes de Oca.

Montes do Oca and del Moral did not respond to emails sent by Forbidden Stories.

Inflated contracts and vanishing logos

While some front companies, such as Sevacom, were awarded a multitude of small contracts that together constituted a large sum, others that Montaño identified were awarded a single contract worth dizzying amounts of money.

Between 2018 and 2019, Instituto C&A Intelligent, S.C. won five contracts totaling nearly two billion pesos (more than €80 million). These two companies supposedly specializing in human resources were responsible for selecting, recruiting, and managing personnel, as well as conducting digital security audits.

“Here, this is where the offices of the company Instituto C&A Intelligent, S.C. are supposed to be located, according to the contracts,” Montaño said in a video report from April 2022. She went to the coastal city of Coatzacoalcos, in the southeast of Mexico, to verify the existence of the company.

Montaño discovered a rundown orange storefront, barricaded by rusty gates that looked as if they had not been opened for a long time. When questioned, a woman living on the second floor of the building said that the last company to occupy the premises had left over two years ago. The rest of the neighborhood was like the store–deserted and abandoned. The domain of the email address of this supposed company is also untraceable. Forbidden Stories tried to contact it, without success.

Contacted by Forbidden Stories, EdoMex provided the consortium with a different address for C&A, located in Toluca, State of Mexico. The logo of the company was displayed on the wall, but according to locals it hadn’t been there for very long. In the middle of May, a truck stopped by and reinstalled the silver plate, which had previously been taken down, neighbors explained. Still, they “never saw anyone going in or out” of the company, and the last remaining offices were emptied “before the pandemic.”

The company Fix Business–which partnered with C&A for three contracts–did appear to exist. Montaño visited the offices located in the city of Puebla.

“This situation is common in cases of corruption: the services are provided by a legal company, and the money is embezzled by another company,” Muna Dora Buchahin Abulhosn, former Director General of the Auditoría Superior de la Federación (ASF), an agency that fights against tax fraud in Mexico, told Forbidden Stories.

Fix Business, a real company, would have served as a guarantor for Instituto C&A Intelligent to embezzle part or all of the money at stake, Abulhosn explained.

When emailed by Forbidden Stories, both companies did not reply.

Another company–Zumby Servicios Profesionales–signed a contract totaling over 2 billion pesos (over €120 million) with the State of Mexico, but it is hard to find any traces of its activity. Much like other suspicious contracts analyzed by the consortium, three of these were signed near the end of the year–on the 30th or 31st of December–a holiday period during which public institutions practically shut down.

In response to a request for comment, the Secretary of Finance, the body responsible for public procurement, explained that the administration does not have “blocked” periods because it must “meet the population’s needs on a daily basis.”

In order to prove its existence, the State of Mexico supplied the consortium with pictures of an office, which is in fact located in a coworking space. The pictures of the company’s fiscal address, also provided by EdoMex, do not match the offices visited by a consortium member at the same address.

Soutenez Forbidden Stories

The “masterful fraud” persists

In 2017, the independent Mexican media outlet Animal Politico published a high-profile investigation exposing a vast corruption network that helped the Mexican Federal Government rake in hundreds of millions of dollars through over a hundred shell companies. This investigation is now known as Estafa Maestra, the “masterful fraud.”

“It was a structured network of senior officials (…) who simulated services for which they received payments,” Abulhosn, whose agency ASF is behind the revelations, said.

Despite the scandal, she says this “modus operandi” continues today with impunity. The investigation of Maria Teresa Montaño Delgado is proof. Abulhosn also underscored the low number of audits the State of Mexico has been subject to.

The government of the EdoMex, which supervises all public administrations in the State, claims that all contracts identified by Forbidden Stories were awarded in compliance with the law. The Secretary of Finance–the only body in charge of purchasing materials and services for all public administrations–stands by the full transparency under which the contracts were drawn up, and insists that all were awarded through public bidding and in compliance with current regulations. They also said that under Mexican law, competitive tenders must be open to companies anywhere in the country.

At the end of this two-year investigation, which greatly impacted her personal and professional life, Montaño was left unsatisfied.

“I would have been able to expose many more things, many more fraudulent companies, if all my work material had not been stolen,” she said. “It seems so unfair to me that resources that are supposed to be used for everyone are being stolen. Calling it out is my way of making this world a better place.”

Today, the investigation into Montaño’s kidnapping is at a standstill. Despite repeatedly contacting the authorities, she has no news about the progress of her case.

For Sara Brimbeuf, Head of Grand Corruption and Illicit Financial Flows at Transparency International France, “this case illustrates the pervasiveness of corruption in Mexico. As of our latest report, Mexico is ranked 126th out of 180 countries in our Corruption Perception Index, with a score of 31–that hasn’t changed for three years.”

As with other corruption cases in Mexico, impunity reigns supreme. “Everyone knows and no one does anything. The State of Mexico is the most corrupt in the country,” concluded Abulhosn.

Our partners’ articles

The Guardian : How a Mexican state siphoned off millions – and a reporter risked her life to expose it

Aristegui Noticias : Las empresas fachada del Estado de México

À lire aussi